A Moore’s Law for Genetics

Sequencing the first human genome cost $3 billion–and it wasn’t actually the genome of a single individual but a composite “everyman” assembled from the DNA of several volunteers. If personalized medicine is to reach its full potential, doctors and researchers need the ability to study an individual’s genome without spending an astronomical sum. Fortunately, sequencing costs have plummeted in the last few years, and now the race is on to see who can deliver the first $1,000 genome–cheap enough to put the cost of sequencing all of an individual’s DNA on a par with many routine medical tests.

Interpreting genomic information is still a very difficult task (see “Drowning in Data”), and we have limited knowledge of how genetic variation affects health. But people will still want to get sequenced, suggests George Church, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and a pioneer in sequencing technology: he says there are 1,500 genes that are considered “medically predictive” and for whose effects mitigating action is possible. A once-in-a-lifetime test could reveal, for example, whether someone couldn’t metabolize a particular drug or should pay careful attention to diet and exercise because of a propensity for heart disease. The $1,000 barrier is expected to be broken in the next year or two, with even cheaper sequencing to follow.

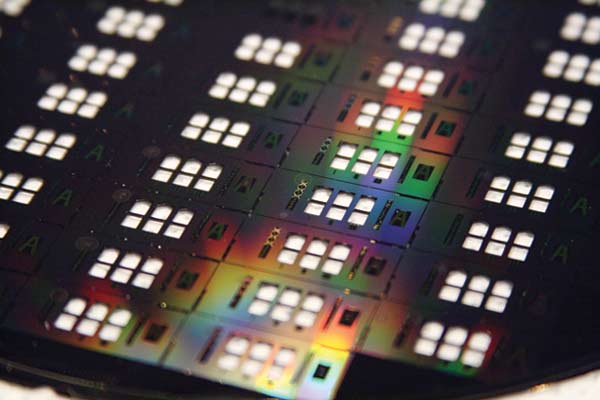

“The key thing that’s driving all of the next-generation sequencing is miniaturization,” says Church. Just as miniaturization steadily decreased the price of computer chips, genome sequencing is getting cheaper as working components are shrunk down and packed more densely together.

Advances include using microfluidics to reduce the volume of chemicals needed for analysis, which saves money because reagents are responsible for a large fraction of sequencing cost. In addition, some companies, such as BioNanomatrix, are developing tiny nanofluidic devices that force molecules along channels about 50 nanometers wide. The company says that using such channels could bring the price of sequencing down to $100 per genome–though it will probably be at least five years before that happens.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.