Behind the Big Apple’s Data Dump

Becoming the latest municipality to fling open stores of data, New York City yesterday released 194 datasets–on everything from restaurant inspections and property sales to traffic data and the locations of laundry facilities. The city also launched a $20,000 competition to develop software applications using this data.

While this may well be the largest release of public data to date by a U.S. city, it still represents a limited opening of the tap–one that doesn’t illuminate governmental budget processes or many negative aspects of city life, such as crime or inferior city services.

A search of the new data site, which went live yesterday afternoon, found no datasets associated with the keywords “crime,” “potholes,” “homeless,” or “campaign contributions.” In the geographical datasets (which represent 93 of the total), the word “fire” produces data showing the location of police and fire stations, but no information about actual fires in the city. Even the word “budget” produced only one hit–a dataset on the city’s adopted budgets. In contrast, Washington, DC, has released performance-tracking and accountability metrics for how capital projects and other programs are faring. The data does, however, include health-department inspection reports of restaurants.

But if you want to know anything about New York City “parks,” you’ll hit the jackpot: 25 separate directories on things like barbecuing sites, handball courts, dog runs, and sidewalk cafes.

“Hopefully what they’ve done is a first step toward the city making all government data, except that which poses a security or privacy concern, available,” says Andrew Rasiej, founder of the Personal Democracy Forum, which tracks the intersection of technology, government, and politics. (Rasiej was also a 2005 candidate for New York City Public Advocate.) “Washington, DC, is way ahead of New York, but the reality is that it’s significant that New York City has finally come to the party and recognized that open data is the future of civic engagement.”

However, he added: “The three most important things people want to know–how to be safe, where my money is being spent, and how the children of our city are doing–are not there. Ten years from now, every city will be doing this by rote. What are we waiting for in New York?”

Beth Noveck, director of the White House open-government initiative, says criticism of the Big Apple’s initial effort is premature. “We need to remind people that Data.gov [the White House data-release site] started with 47 datasets, quickly jumped to 100,000 and is taking off from there,” she says. “So it’s wonderful that New York started this and followed the president’s lead in making government more open.” She expects the city’s effort to grow substantially.

City officials say the release represents everything they could pull together from 30 agencies in the four months since Mayor Michael Bloomberg promised the release in June. The city will continually add to the datasets, says Kristy Sundjaja, a vice president at the city’s Economic Development Corporation. She adds that through its NYC BigApps competition, the city is encouraging contestants to combine city data with data from other sources. Examples might, in theory, include mashups of taxi-license data with crowd-sourced citizen complaints about taxi conditions.

“We are definitely open to any application ideas that will make it easier for citizens and visitors to New York to live and work and have fun,” Sundjaja says. “That is the theme of this year’s competition.” Details of the contest, which will offer $20,000 in prizes, are viewable here.

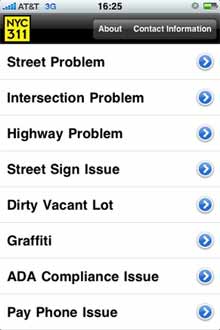

New York City has already created an iPhone app interface for its popular 311 service system, which citizens can use to learn about city services and report nonemergency problems like potholes and broken streetlights.

“The remarkable thing overall is that we are going from the default of keeping information private to the default of making it public.” says David Weinberger, a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, who and was an Internet advisor to Howard Dean during his 2004 presidential campaign. “Rather than having to put in a Freedom of Information Act request for everything you want, the approach has become, ‘We are going to put out more than you can ever use.’”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.