Bringing Graphene to Market

A startup company in Jessup, MD, hopes later this year to bring to market one of the first products based on the nanomaterial graphene. Vorbeck Materials is making conductive inks based on graphene that can be used to print RFID antennas and electrical contacts for flexible displays. The company, which is banking on the low cost of the graphene inks, has an agreement with the German chemical giant BASF and last month received $5.1 million in financing from private-investment firm Stoneham Partners.

Since it was first created in the lab in 2004, graphene has been hailed as a wonder material: the two-dimensional sheets of carbon atoms are the strongest material ever tested, and graphene’s electrical properties make it a potential replacement for silicon in faster computer chips. Synthesizing pristine graphene of the quality needed to make transistors, though, remains a painstaking process that, as yet, can’t be done on an industrial scale, though researchers are working on this problem.

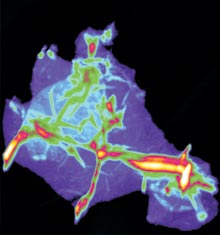

Vorbeck Materials is making what company scientific advisor Ilhan Aksay calls “defective” graphene in large quantities. Though the electrical properties of the graphene aren’t good enough to support transistors, it’s still strong and conductive.

Vorbeck Materials licensed their method for making “crumpled” graphene from Aksay, a professor of chemical engineering at Princeton University. Vorbeck Materials says the inks made with this crumpled graphene are conductive and cheap enough to compete with silver and carbon inks currently used in displays and RFID-tag antennas. (Another startup working on defective graphene, Graphene Energy of Austin, TX, is using a similar form of the material to make electrodes for ultracapacitors.)

Aksay’s method begins by oxidizing the graphite with acids, then separating it into atom-thin sheets. The expanded graphite is then rapidly heated, creating carbon dioxide gas that builds up pressure, forcing the graphene sheets apart. This process is common, says Aksay, but his research group developed monitoring methods to improve the yield and ensure that the graphene sheets completely separate. The sheets are then heated to remove the oxygen groups. “The conductivity nears that of pristine graphene, but the sheets are crumpled so they don’t stack together again,” says Aksay. The resulting powder can be added to a solvent to make inks or added to polymers to make composites such as tough tire rubber.

Most conductive inks on the market are made out of silver particles. These inks can be printed using cheap techniques but the inks themselves are expensive. Silver is used instead of cheaper metals because it is less prone to oxidation. Silver inks are more conductive than Vorbeck’s graphene ink, says company president John Lettow, but also much more expensive. They also have to be heat-treated after they’re applied, which means they can’t be printed on polymers and other heat-sensitive materials. Graphene ink requires no heat treatment and is more conductive than other carbon-based alternatives to silver inks.

Potential applications for the inks, Lettow says, include antennas for cheap RFID tags printed on paper and electrical contacts for displays. Nick Colaneri, director of the Flexible Display Center at Arizona State University, says the inks’ conductivity may limit their application in displays to low-resolution devices.

Vorbeck Materials is in talks with electronics manufacturers to develop inks to their specifications. Lettow says the company will begin selling graphene inks by the end of the year.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.