Brain Surgery Using Sound Waves

A new ultrasound device, used in conjunction with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), allows neurosurgeons to precisely burn out small pieces of malfunctioning brain tissue without cutting the skin or opening the skull. A preliminary study from Switzerland involving nine patients with chronic pain shows that the technology can be used safely in humans. The researchers now aim to test it in patients with other disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease.

“The groundbreaking finding here is that you can make lesions deep in the brain–through the intact skull and skin–with extreme precision and accuracy and safety,” says Neal Kassell, a neurosurgeon at the University of Virginia. Kassell, who was not directly involved in the study, is chairman of the Focused Ultrasound Surgery Foundation, a nonprofit based in Charlottesville, VA, that was founded to develop new applications for focused ultrasound.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is different from the ultrasound used for diagnostic purposes, such as prenatal screening. Using a specialized device, high-intensity ultrasound beams are focused onto a small piece of diseased tissue, heating it up and destroying it. The technology is currently used to ablate uterine fibroids–small benign tumors in the uterus–and it’s in clinical testing for removing tumors from breast and other cancers. Now InSightec, an ultrasound technology company headquartered in Israel, has developed an experimental HIFU device designed to target the brain.

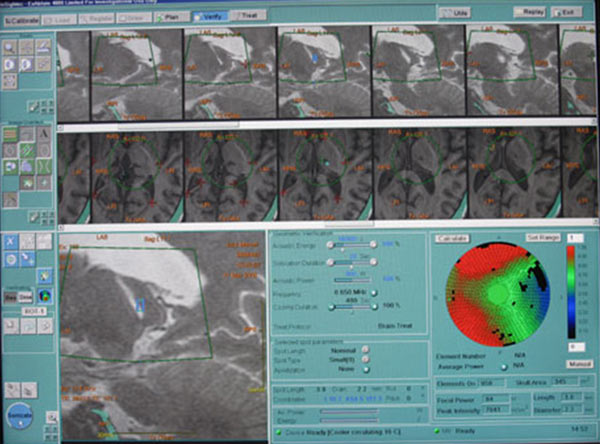

The major challenge in using ultrasound in the brain is figuring out how to focus the beams through the skull, which absorbs energy from the sound waves and distorts their path. The InSightec device consists of an array of more than 1,000 ultrasound transducers, each of which can be individually focused. “You take a CT scan of the patient’s head and tailor the acoustic beam to focus through the skull,” says Eyal Zadicario, head of InSightec’s neurology program. The device also has a built-in cooling system to prevent the skull from overheating.

The ultrasound beams are focused on a specific point in the brain–the exact location depends on the condition being treated–that absorbs the energy and converts it to heat. This raises the temperature to about 130 degrees Fahrenheit and kills the cells in a region approximately 10 cubic millimeters in volume. The entire system is integrated with a magnetic resonance scanner, which allows neurosurgeons to make sure they target the correct piece of brain tissue. “Thermal images acquired in real time during the treatment allow the surgeon to see where and to what extent the rise in temperature is achieved,” says Zadicario.

The Swiss study, published this month in the Annals of Neurology, tested the technology on nine patients with chronic debilitating pain that did not respond to medication. The traditional treatment for these patients is to use one of two methods to destroy a small part of the thalamus, a structure that relays messages between different brain areas. Surgeons either use radiofrequency ablation, in which an electrode is inserted into the brain through a hole in the skull, or they use focused radiosurgery, a noninvasive procedure in which a focused beam of ionizing radiation is delivered to the target tissue. Zadicario says HIFU has advantages over radiosurgery because the effects of killing tissue with radiation can take weeks to months, whereas the thermal approach is immediate. Adds Kassell, “The precision and accuracy [are] considerably greater with ultrasound, and it should be in principle safer in the long run.”

According to the new study, all nine patients reported immediate pain relief after the outpatient procedure and were up and about soon afterward. “Two patients had a glass of Proseco [wine] with us,” says Ernst Martin, director of the Magnetic Resonance Center at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich and lead author of the study. The patients did report feeling a few seconds of tingling or dizziness, and in one case a brief headache, as the targeted tissue heated up, he says. But none experienced neurological problems or other side effects after surgery.

“This will give a lot of impetus for manufacturers of focused ultrasound equipment to get interested in the brain,” says Kassell. An experimental version of InSightec’s ultrasound device is currently being tested in five medical centers around the globe. In addition to using it with Parkinson’s patients and those who suffer other movement disorders, scientists plan to test the technology as a treatment for brain tumors, epilepsy, and stroke.

One downside of HIFU compared to the more invasive neurosurgeries performed with an electrode is that surgeons are unable to functionally test whether they have targeted the correct part of the brain. During traditional surgery for Parkinson’s, for example, the neurosurgeon stimulates the target area with the electrode to make sure he or she has identified the piece of the brain responsible for the patient’s motor problems, and then kills that piece of tissue.

“Not every functional neurosurgeon will accept this [new approach], because you cannot do a test before the lesion is made,” says Ferenc Jolensz, director of the Division of MRI and Image Guided Therapy Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Jolensz and collaborator Seung-Schik Yoo are developing ways to use HIFU to modulate brain activity in a localized area, which would enable functional testing of the target area before it is destroyed. Jolensz is also studying HIFU for brain surgery and has tested the technology on four patients with brain tumors, though the results have not yet been published.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.