Toward a Universal Flu Vaccine

Flu shots have to be reformulated every year, thanks to the constantly mutated virus. And the annual vaccine won’t protect against more deadly strains, like the H5N1 bird flu. But that may soon change: scientists have now developed antibody proteins that can neutralize different strains of the influenza virus, including the deadly H5N1 bird flu, the virus behind the 1918 epidemic, and common seasonal strains. These new antibodies target part of the virus that is shared between different strains and thus appears to be broadly effective. The research was published on Sunday in the journal Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

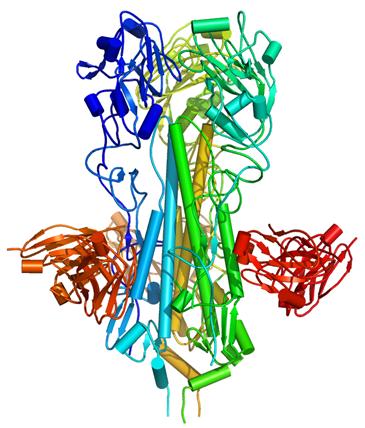

and blue) on the H5 influenza virus H5, bound to a

neutralizing antibody (red).

Credit: William C. Hwang

According to an article in Nature,

The antibodies also give researchers clues about how to develop new vaccines. “This opens up the avenue of thinking about universal influenza vaccines, which has not been realistic before”, says Peter Palese, an influenza expert at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York who was not involved in the work.

A vaccine using this technology could theoretically be used to protect against various types of flu, as well as to treat the virus once a person is infected. Scientists who developed the antibodies say that they hope to have a candidate vaccine to test in humans within the next three years.

But not everyone is as optimistic about the possibilities. According to an article in the New York Times,

Henry L. Niman, a biochemist who tracks flu mutations, was skeptical, arguing that human immune systems would have long ago eliminated flu were the virus as vulnerable in one spot as this discovery suggested. Also, he noted, protecting the mice in the study took huge doses of antibodies, which are expensive and cumbersome to infuse.

[…]

The research began by screening a library of 27 billion antibodies he had created, looking for ones that take aim at the hemagglutinin “spikes” on the shells of flu viruses … The flu virus uses the lollipop-shaped hemagglutinin spike to invade nose and lung cells. There are 16 known types of spikes, H1 through H16.

The spike’s tip mutates constantly, which is why flu shots have to be reformulated each year. But the team found a way to expose the spike’s neck, which apparently does not mutate, and picked antibodies that clamped onto it. Once its neck is clamped, a spike can still penetrate a human cell, but it cannot unfold to inject the genetic instructions that take over the cell’s machinery to make more virus. The team then turned the antibodies into full-length immunoglobulins and tested them in mice.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.