Beijing’s Smog Experiment

One of the most watched projects during the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, along with the construction of the Bird’s Nest Stadium and the glowing Aquatics Cube, was the Chinese government’s efforts to cut emissions by 60 percent in the city. It has been a colossal undertaking in an area where air-pollution is five times higher than World Health Organization safety standards and smog can get so dense that it sometimes occludes the sun. The effort has involved ordering half of the city’s cars off the roads and temporarily moving or closing dozens of steel mills, foundries, and factories across the capital.

But such a dramatic decrease in pollution could provide more than just healthier conditions for competing athletes. It may also afford scientists a rare opportunity to see how climate change responds to such a massive adjustment in emissions.

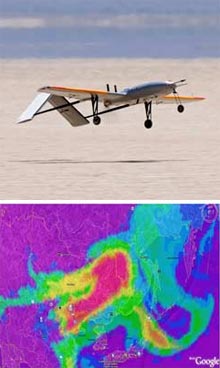

A team led by Veerabhadran Ramanathan, a climate and atmospheric scientist at the University of California, San Diego, will spend the next six weeks flying autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles (AUAVs) downwind of Beijing to measure emissions reductions. “By cutting down on the pollution over Beijing during the Olympics, the Chinese have created a huge natural laboratory for understanding how pollution impacts climate,” Ramanathan says. He and collaborators at Seoul National University, in South Korea, have packed an assortment of miniature instruments into 30-kilogram, three-metre-wide AUAVs and set up a research station on South Korea’s Cheju Island, about 500 kilometers south of Beijing.

Using the island as their base, the researchers are flying the small aircraft in groups of three: over, under, and through the polluted plume as it travels past the island. Because different layers of wind carry air from different regions, and because the wind currents change direction, they can also sample air from other parts of China that have not implemented emissions cutbacks. “We fly up to 12,000 feet,” Ramanathan says, “so I don’t have to go anywhere. The mountain comes to Mohammed.”

The team will also be running simultaneous flights in California, to see how far away they can detect the plume. “We want to see what the global impact of this one city is,” he says. Ramanathan is especially interested in unraveling the relationship between air pollution and climate change, since prior research from his lab has shown that airborne particles in emissions can mask up to half of the greenhouse effect by reflecting sunlight back into space.

The researchers plan to combine the AUAV measurements with those from NASA satellites and back-calculated wind trajectories. The results should give them a clearer picture of what the air looks like and whether more sunlight is reaching the earth’s surface as a result of the decreased emissions.

Ramanathan is concerned that worldwide efforts to reduce air pollution over the next few decades could as much as double the rate of global warming. With a huge number of unknowns in this equation, he’s hoping that their work can help him better understand the problem.

In order to accurately measure the impact of Beijing’s emissions reductions, the scientists must also know what normal air pollution conditions would be. Greg Carmichael, an environmental and chemical engineer at the University of Iowa, has been modeling Beijing’s emissions and creating estimates for what the pollution levels would have been pre-cutbacks, as well as estimates for what they should be now.

Carmichael can’t give specifics until the final numbers are in, but he can say that the air quality in Beijing is somewhere between 10 and 50 percent better than it would have been without the strict controls. This is a wide margin to be sure, he says, “but it’s a very complex system. And to take Beijing and be able to reduce your emissions by 50 percent is a huge success. It’s a difficult thing to do.” Los Angeles and other cities have spent 20 years or more trying to improve their air quality, he notes, and they still have a ways to go.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.