Making Phones Polite

There’s no doubt that mobile phones are becoming more like computers as they gain functions, storage capacity, and processor speed. But even with Internet access and touch screens, these gadgets are still dumb machines. They know nothing about the person who uses them, and in particular, they don’t know when it’s appropriate to interrupt.

Now, researchers at Intel have developed software that could help make handhelds more considerate. The software is able to detect and record conversations, but crucially, it does so in a privacy-sensitive manner so that the actual spoken words can’t be retrieved. “Our goal is to be able to collect data about interactions and conversations that happen spontaneously … and have a balance between privacy and the information we can get from recorded data,” says Tanzeem Choudhury, a researcher at Intel Labs Seattle.

The researchers capture information about how human speech is produced, says Choudhury, rather than information about the words themselves. Participants in the study wore a pager-size device with a microphone, some memory, and a processor that processed the audio so that features such as volume, pitch, tone, and rate of speech could be estimated. Surprisingly, Choudhury says, this information can speak volumes about a person’s situation, mood, and social network. “You cannot get what is being said,” she says, but “they allow us to make different types of inferences.”

For example, the amount of time a person speaks and the number of interruptions in a conversation can indicate the status of the people in the conversation, Choudhury says. For instance, a boss-and-employee interaction would likely be a conversation in which one person does most of the talking and there are few interruptions. Conversely, if a conversation is dynamic, and there is a lot of overlapping speech, it’s most likely a casual or social conversation. In addition, Choudhury says, people’s mood can be inferred because speaking rate, loudness, and pitch change when they’re angry, happy, excited, sad, and so on.

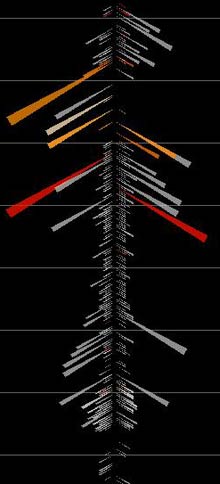

Multimedia

View images of the device, how it can be worn, and the data it produces.

The Intel team isn’t the first that has collected conversations to gain insight into social interaction, says Nelson Morgan, director of the International Computer Science Institute and a professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Berkeley. For about a decade, researchers have recorded business meetings, he says, with the hope of analyzing the social structure and determining who made decisions, who was dominant, and what the key ideas of the gathering were. But not as much work has focused on trying to analyze impromptu conversations, and it is novel, Morgan notes, to consider privacy in the data-collection process. “That’s a neat idea, and they did very well with it,” he says.

The Intel study analyzed 24 University of Washington graduate students’ conversations over the course of a school year. The idea was to capture a week’s worth of data each month for nine months so that the researchers could have day-to-day interactions and snapshots of conversations over time. In order to make sense of all the data, the researchers collected extra information from the participants, using surveys. But since the conversations were spontaneous, it wasn’t possible to do so for all the collected conversations. So Choudhury’s team gathered a smaller data set from five people whose words were recorded by the software during their conversation; data from this set was used as a benchmark to measure conversation features. The results will be presented at Interspeech 2007, a conference held later this month in Antwerp, Belgium.

Choudhury says that it would also be fairly straightforward to integrate the researchers’ software into a mobile device so that it could infer a person’s “presence,” a concept used in instant messaging to denote whether or not a person is available to talk. “There’s been a lot of work showing that interruptability or situational awareness in our devices can be very useful,” she says. And people are becoming more comfortable with the idea of broadcasting information about themselves to the world, as evidenced by the popularity of the social-networking platform Facebook and microblogging tools such as Twitter and Jaiku.

Still, Intel doesn’t have immediate plans to put the software in mobile devices, and there are still some technical hurdles to overcome in order to do so. Choudhury says that her software is significantly more precise than previous software for detecting and segmenting conversations, and it’s able to detect a speaker in a conversation with more than 90 percent precision. But the accuracy of other aspects of the system–such as inferring mood–is still being determined. And no one has tested how these features would be practically integrated into a mobile device. Indeed, an individual user might need to set up rules for her phone, allowing people to contact her only when she’s in certain situations. In addition, most phones couldn’t yet analyze all the data in real time. Today’s phones, Choudhury says, could reasonably determine the structure of a conversation–when a person is talking and for how long–but more detailed analysis would require more processing power than is currently available in phones.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.