Robots Act as Soccer Commentators

As national soccer teams head into the second round of the World Cup this week in Germany, they’re playing in the wake of RoboCup 2006, held last week in Bremen, Germany. Organized by the RoboCup Federation, these games, in which robots on wheels and legs compete in soccer “matches,” are sponsored by a host of companies, including Microsoft. It might not get the fanfare of the World Cup, but this year RoboCup drew more than 400 teams from 36 countries.

In 2006, though, a new twist was added to the event: robots not only played in the games, they also called the action.

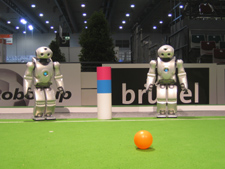

The two new announcers are biped robots made by Sony and programmed by a team of computer scientists at Carnegie Mellon University, led by professor Manuela Veloso. Standing around two-and-a-half feet tall, the robots were originally built to showcase Sony’s robotic technology; they can perceive in three dimensions, recognize faces and colors, and talk in multiple languages.

Veloso and coworkers gave two of these Sony robots, which they named Ami and Sango, a second career, by programming them to be RoboCup sportscasters. Veloso, a computer scientist with a special interest in robots that can observe, points out that the event’s focus is artificial intelligence, not soccer, and that this “universally loved game” invites researchers to make robots that work in teams and respond to changing situations.

“Robot soccer is very dynamic and uncertain,” Veloso says. As for the commentators, she says that humans still called and refereed the matches, and she “was curious about doing another task that was robot based.”

The first challenge for Veloso’s group was getting the robots to see a soccer game. They started with a ball. Each robot’s “eyes,” which are video cameras, can recognize colors, including an orange soccer ball. Veloso’s students had already programmed many Sony robotic dogs to find and follow this orange ball while playing in the RoboCup. Now, over four months, they programmed the bipeds to track the ball with their eyes, with heads and bodies following, so that they face the action.

Meanwhile, the robots’ onboard computers compare frames of video, recording changes in the ball’s location and computing its speed, and sometimes announcing it (“The ball went 1.2 meters per second”). If the ball moves faster, they might comment “Nice kick.” And if a player scores, the robo-announcers can recognize it, then search internal lists for phrases or actions to celebrate, such as waving their arms or saying “Awesome goal!”

So far, the robots can visualize only the ball and goal, but more information – fouls, the score, and time left in a half – can be sent to them wirelessly. Based on these inputs, they scan other lists for things to say and do. One might announce, “One minute left in the half.” Or, if the off-field computer tells the other one that a player has kicked the ball out of bounds, it might deliver an explanation of the RoboCup rules.

During unexpected events, say, if a player falls down, someone can type an appropriate comment for the robots to utter (“Ouch!”). The announcers read these phrases using a speech synthesizer. But Veloso uses this trick sparingly, relying mainly on the robots to choose their own actions. “We don’t want to make them sound like us. We want to see what they say by themselves,” she says.

The two commentators are also programmed to coordinate their actions. Ami and Sango each watch half of the field, since neither can see it all. When one sees a play that the other misses, it sends a wireless message to its partner. Then each decides how to react; after a goal, Ami might dance while Sango says “Score!” They won’t repeat one another or talk simultaneously, but instead can interrupt each other. This robot-to-robot exchange – while each is still watching the field and taking data from computers – is “challenging,” Veloso says.

The robots can’t learn yet – they don’t alter their behavior based on what the fans seem to like. But they can adapt to dramatic situations on the field. The programmers have assigned numerical weight to happenings like tie scores, for instance, and if a goal follows a tie, the robots choose more enthusiastic cheers.

Last week, Ami and Sango called RoboCup matches between Sony robot dogs, which are not fast-paced. In other RoboCup games, where the ball races across the field, Veloso says the “information is changing too fast.” To call those matches, her group would need to write faster-running programs, she says.

Veloso, who has attended the RoboCup for 10 years, says the event’s technology advances each time. “In videos from ten years ago and the videos now, there’s a great difference,” she says. The robot players are now “more reliable and they perform…soccer tasks more intelligently.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.