Computing with Lasers Could Power Up Genomics and AI

As the cost of sequencing a person’s genome plummets, demand for the computing power needed to make sense of the genetic information is growing. Nicholas New hopes some of it will be worked on by a processor that parses data using laser light, built by his U.K. startup, Optalysys.

New says his company’s exotic approach to crunching data can dramatically upgrade a conventional computer by taking over some of the most demanding work in applications such as genomics and simulating weather. “The grunt work can be done by the optics,” he says.

Researchers have worked on the idea of using optics rather than electronics to process data for decades, with little commercial traction. But New argues that it is now needed because manufacturers such as Intel admit that they can’t keep improving conventional chips at the pace they used to (see “Moore’s Law Is Dead. Now What?”).

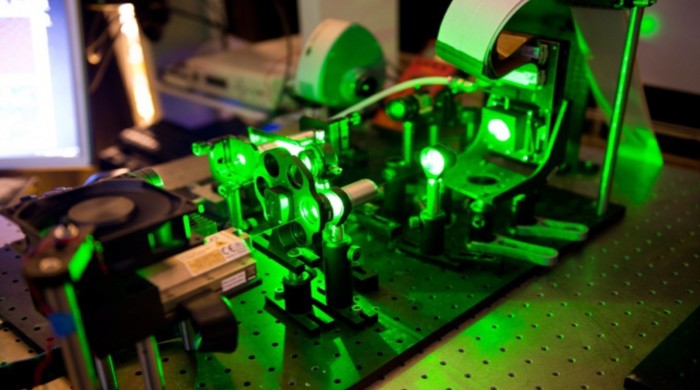

Optalysys’s technology performs a mathematical function called the Fourier transform by encoding data, say a genome sequence, into a laser beam. The data can be manipulated by making light waves in the beam interfere with one another, performing the calculation by exploiting the physics of light, and generating a pattern that encodes the result. The pattern is read by a camera sensor and fed back into a conventional computer’s electronic circuits. The optical approach is faster because it achieves in a single step what would take many operations of an electronic computer, says New.

The technology was enabled by the consumer electronics industry driving down the cost of components called spatial light modulators, which are used to control light inside projectors. The company plans to release its first product next year, aimed at high-performance computers used for processing genomic data. It will take the form of a PCI express card, a standard component used to upgrade PCs or servers usually used for graphics processors. Optalysys is also working on a Pentagon research project investigating technologies that might shrink supercomputers to desktop size, and a European project on improving weather simulations.

French startup LightOn, founded earlier this year, has also built a system that uses optical tricks to process data being carried by laser light. The company is targeting a trick used in machine learning that compresses information by multiplying it with random data.

That technique is useful, but onerous for conventional computers working with large data sets, says Laurent Daudet, LightOn’s chief technology officer and a professor of physics at the Université Paris Diderot. His system gets the same effect more easily by exploiting the random scattering that naturally occurs when light passes through translucent material.

“Computers really suck at this, [but] you can use nature to do it instead,” says Daudet. He and LightOn’s two other founders published results last year showing how that works. The company is working to show its system can perform other operations, too, and aims to put a new prototype online as a cloud service for others to experiment with, says Daudet.

The timing is good for these startups. Recognition that existing chip designs will no longer improve at the exponential pace they used to is making the industry more open to new ideas, says Horst Simon, deputy director of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “As conventional chips don’t get faster any more, alternative routes look more attractive,” says Simon.

Those alternative routes include quantum computers and chip designs specialized for AI, as well as optical computing systems. Simon doubts that optical technology will take over all kinds of computing, but says it might finally find a practical place. “There may be niche applications where its performance makes sense,” he says.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.