Governments Around the World Deny Internet Access to Political Opponents

Whether or not your ethnic group has political power in the country where you live is a crucial factor determining your access to the Internet, according to a new analysis.

The effect varies from country to country, and is much less pronounced in democratic nations. But the study, published today in Science, suggests that besides censorship, another way national governments prevent opposing groups from organizing online is by denying them Internet access in the first place, says Nils Weidmann, a professor of political science at the University of Konstanz in Germany.

Internet access is clearly linked to individuals’ socioeconomic status and the level of development where they live. These factors contribute to “digital divides” seen throughout the world. In the new analysis, Weidmann and his coauthors aimed to shed light on a factor that isn’t as well understood: political divisions between ethnic groups.

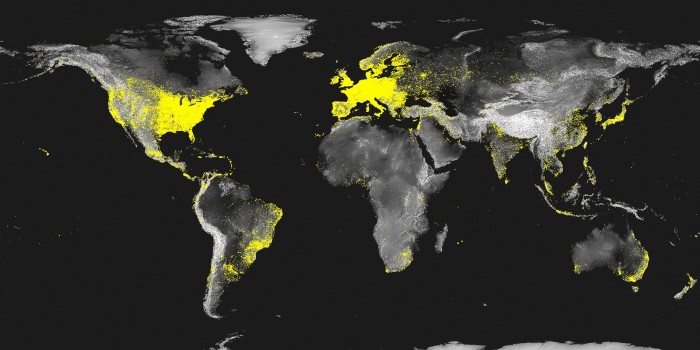

To achieve this, the group first had to create a new global map reflecting how Internet access varies across geographic regions within individual nations. For many countries, especially autocracies, such “subnational data” is difficult to find or is simply not available, says Weidmann. So he and his colleagues used data from a Swiss Internet service provider that handles huge amounts of global traffic, and information from a database that tracks the global Internet routing system, to create a global database of “subnetworks,” or small units of the Internet that correspond to just a few hundred IP addresses. They used a geolocation database to map those subnetworks. The map above highlights all the active subnetworks in the world in 2012.

The researchers then turned to the so-called Ethnic Power Relations list, a database that categorizes the world’s ethnic groups according to their political relevance in their home countries, distinguishing between politically “included” vs. “excluded” groups. Using this distinction, and geographic information pinpointing the settlement regions of individual groups, Weidmann and colleagues determined how Internet penetration rates relate to political power. (About a third of the groups in the list were too widely dispersed to be included in the analysis.)

They concluded that excluded groups had significantly lower access compared to the groups in power, and that this can’t be explained by other economic or geographic factors (like living in rural vs. urban areas). Weidmann says the results add a new layer to our understanding of how national governments control Internet use. “You don’t have to censor if the opposition doesn’t get access at all.” He says organizations aiming to increase Internet access for humanitarian reasons must bear that in mind, and be careful not to reinforce such political bias.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.