The Birth of an IT Powerhouse

In 1884, the Mahratta, an Indian nationalist newspaper in the city then known as Poona, ran a three-part series under the title “Model Institute of Technology,” containing excerpts from MIT’s annual report and noting its relevance to India. The vision articulated by the Institute’s founder, William Barton Rogers—that scientific training could strengthen a nation’s industrial base—had a special resonance for a group of Indians desperate to catch up with Britain and the United States and become part of the industrial world. Even though MIT was still struggling to establish itself, the Mahratta’s editors asserted that it was the “best conducted institute in the world.”

The British colonial government ignored the Mahratta’s plea for a greater emphasis on technical education, but six decades later, the Viceroy of India commissioned the British Nobel laureate A. V. Hill to visit India and make recommendations for its scientific and technological future. Hill’s 1944 report included a call to found a “few colleges of Technology on a really great scale like the MIT at Cambridge, Mass.” And with that suggestion, MIT became the model for the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT). In the early 1960s, Indian government leaders seeking American assistance to develop the IIT at Kanpur turned down an offer of help from Ohio State, insisting that only MIT could produce the kind of institute they wanted. More than 50 years later, the IITs enjoy a global reputation, and IIT Bombay has its own “Infinite Corridor.”

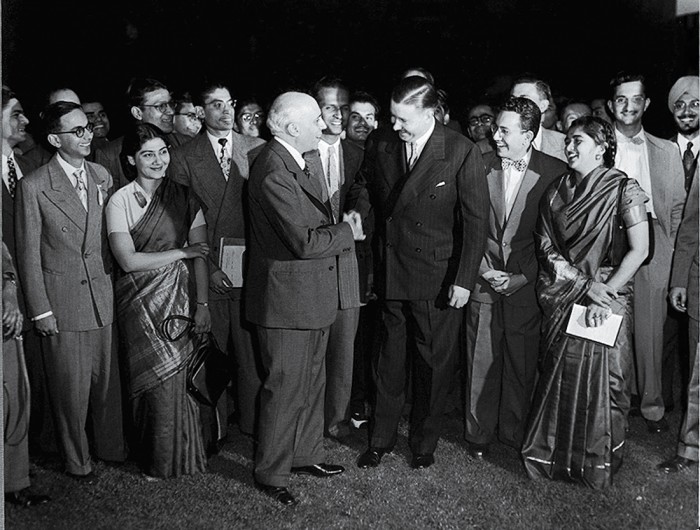

In 1945 almost 500 Indians applied for admission to the Institute, so strong was the belief that MIT training could transform their country. In 1949, two years after India had become independent, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru visited MIT, meeting with President James Killian and Indian students. Although much had changed about both MIT and India since the 1884 articles in the Mahratta, the dream of building a new nation based on technology had not. In a speech, Nehru asserted that the history of a nation must be considered “from a technological viewpoint,” and he claimed that India’s deficits in this area had left it vulnerable to colonization. Although he had studied law himself, he declared that “India has too many lawyers and too few engineers,” urging the students to “work hard to make India once again a first-class nation.”

Indians trained at MIT played a major role in the newly independent country, designing steel mills, setting up and leading new government laboratories, serving as leading figures in the atomic and space programs, and establishing professional societies. Meanwhile, India’s leading business families, some with centuries of experience, decided that the old ways of training their heirs were no longer sufficient and sent their children to MIT to equip them to lead their businesses into a new era.

Nehru could not have foreseen the role that MIT would play in bringing the new technology of computing to India, however. In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of Indian students at MIT funded their education as assistants in the Institute’s many high-profile computing efforts, such as Project MAC, the hugely influential computer time-sharing project. When they returned home, some thought about how computers might be used in India, as quixotic as that might have seemed in a country lagging in most areas of technology. These graduates played a fundamental role in establishing IT outsourcing in India. Three young MIT graduates founded Tata Consultancy Services, today India’s largest IT outsourcing firm, and by 1991 five of India’s top 10 software exporters had an MIT graduate in their genealogy.

Today, India has a $146 billion IT industry, and Indian engineers have had a major impact in the United States as well: for example, Subra Suresh, ScD ’81, a former MIT dean of engineering and director of the National Science Foundation, is now president of Carnegie Mellon University. The dreams of a group of late-19th-century Indians had much to do with this success. But 26 percent of Indians today remain illiterate, and more than half lack access to indoor plumbing. While the country has demonstrated its talent for producing skilled engineers, technology has not proved to be the solution to all of its problems.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.