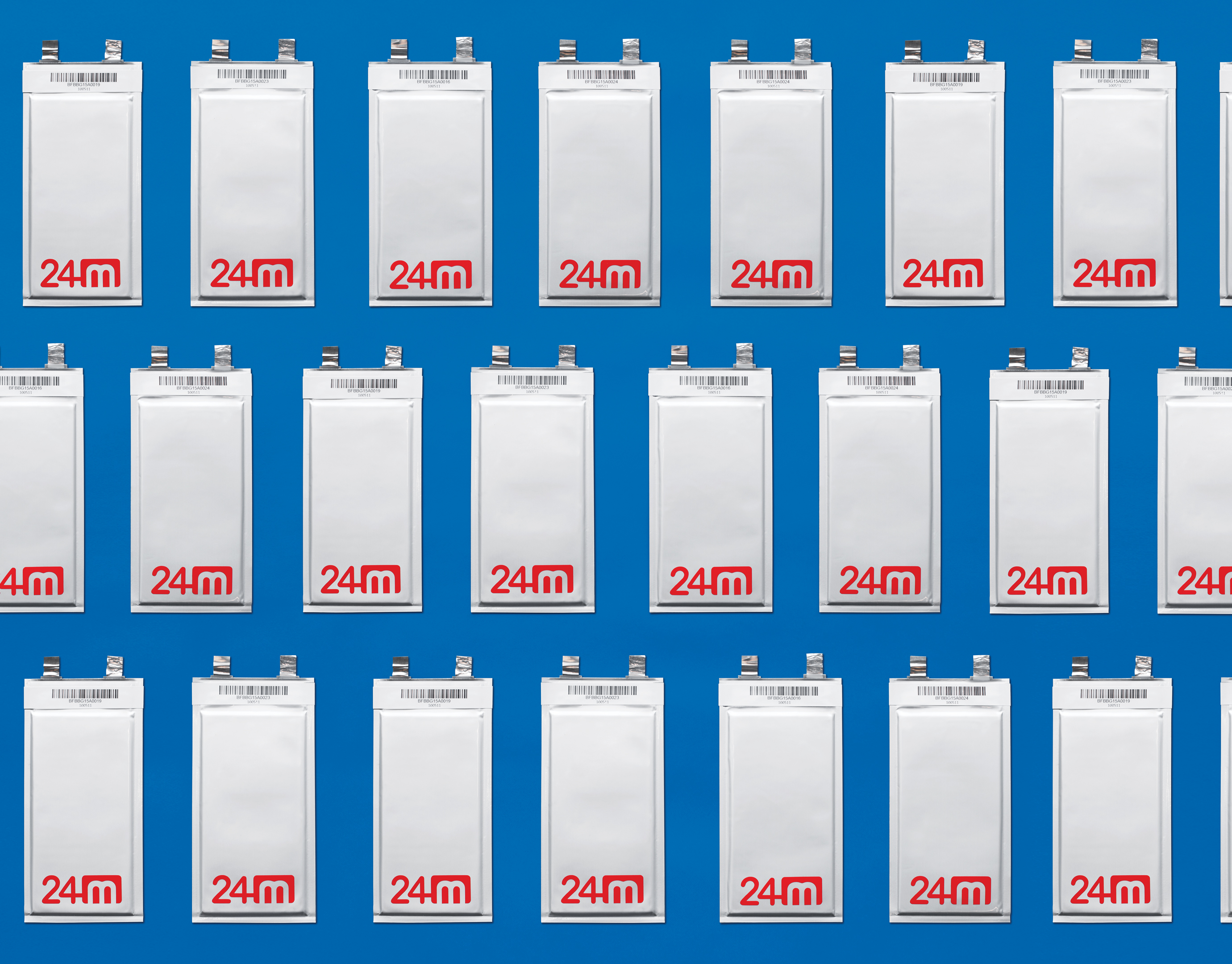

24M’s Batteries Could Better Harness Wind and Solar Power

Lithium-ion batteries power everything from smartphones to electric vehicles. They’re well suited to the job because they are smaller and lighter, charge faster, and last longer than other batteries. But they are also complex and thus costly to make, which has stymied mass adoption of electric transportation and large-scale energy storage.

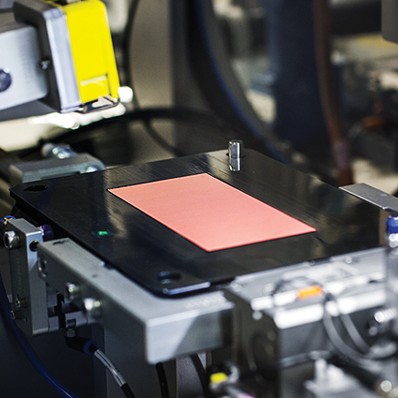

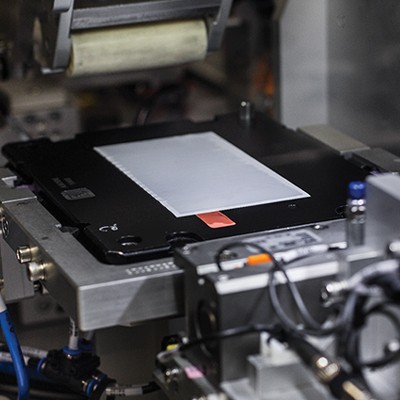

Yet-Ming Chiang thinks his startup 24M has the answer. The key is a semisolid electrode. In a conventional lithium--ion battery, many thin layers of electrodes are stacked or rolled together to produce a cell. “Lithium-ion batteries are the only product I know of besides baklava where you stack so many thin layers to build up volume,” says Chiang, who is a cofounder and chief scientist at 24M as well as a professor of materials science at MIT. “Our goal is to make a lithium-ion battery through the simplest process possible.”

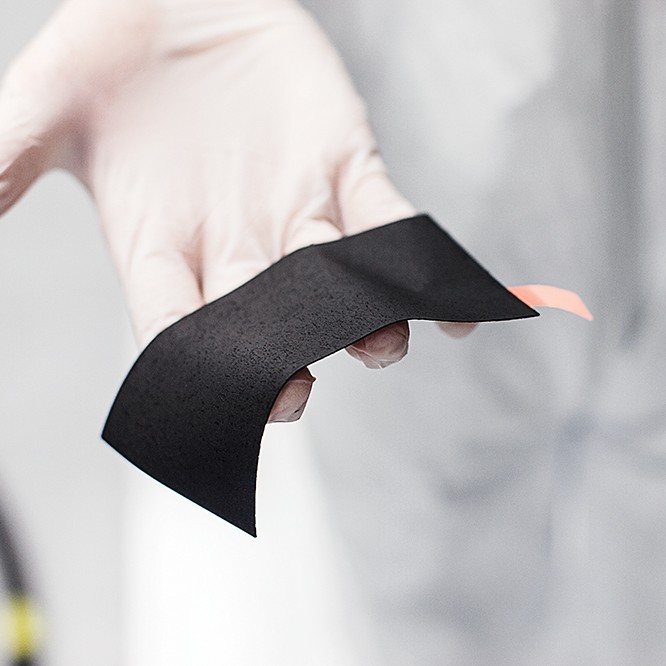

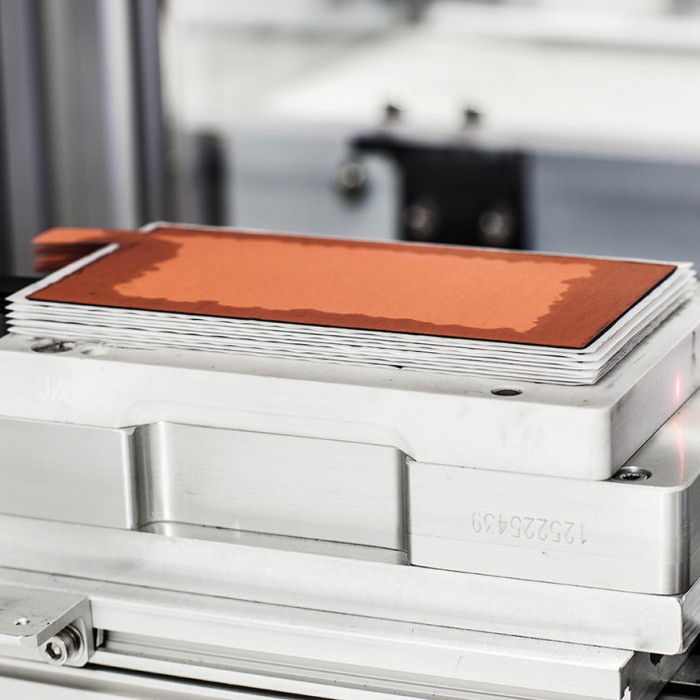

Chiang’s innovation, which was developed in his MIT lab, is an electrode formed by mixing powders with a liquid electrolyte to make a gooey slurry. The design enables 24M to increase the amount of energy-storing material in a battery and give it 15 to 25 percent more capacity than conventional lithium-ion batteries of the same size.

See the Rest of the Package

50 Smartest Companies

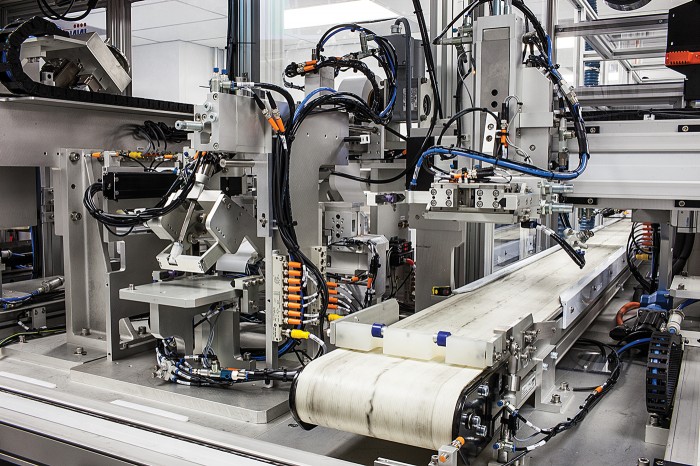

The new design is also faster and cheaper to make. Typical large factories for making lithium-ion batteries cost about $100 million to build, in part because specialized machines are needed to coat, dry, cut, and compress the electrode film. Since its semisolid electrode doesn’t require these steps, 24M says, its batteries could be produced in one-fifth the time and in much smaller plants.

If its technology succeeds, 24M could be among the first companies to reduce the cost of lithium-ion battery cells to less than $100 per kilowatt-hour, from $200 to $250 today. That is the point at which electric cars could compete on cost with internal-combustion vehicles.

To hit that target by 2020, 24M must scale up from its existing pilot manufacturing line in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to high-volume fabrication. The company plans to build a factory in 2017, probably in partnership with a large industrial company, and launch its first product in early 2018. It hopes utilities will buy its batteries to store electricity from wind and solar farms and deliver power during peak-demand hours.

The company is also talking to electric--vehicle makers, but it considers EVs a secondary focus. It’s understandable that Chiang would tread carefully in that market. A123 Systems, a battery company he cofounded, filed for bankruptcy protection in 2012 after spending too much money building big battery plants to supply carmakers. In contrast, Chiang says, 24M’s manufacturing technologies are designed to be modular and more efficiently scaled up if necessary.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.