Go Inside TriAlpha, A Startup Pursuing the Ideal Power Source

No energy technology is more tantalizing than fusion, but no energy technology has proved more disappointing. So how has a fusion company in Southern California raised nearly half a billion dollars from the likes of Goldman Sachs and Paul Allen? Does it actually see a way to build a reactor that could generate vast amounts of clean power, even while other fusion projects have perpetually remained 20 years away from reality?

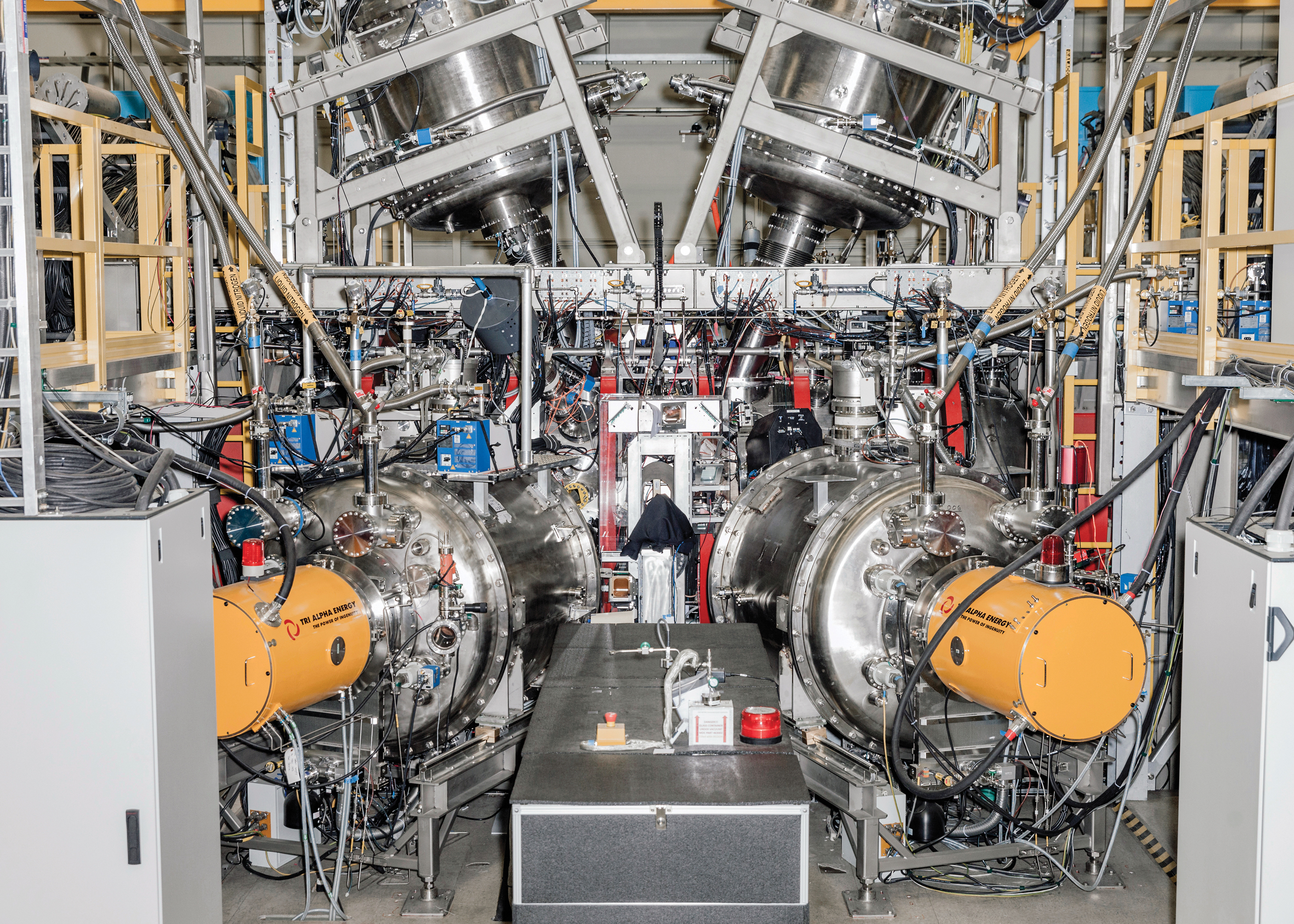

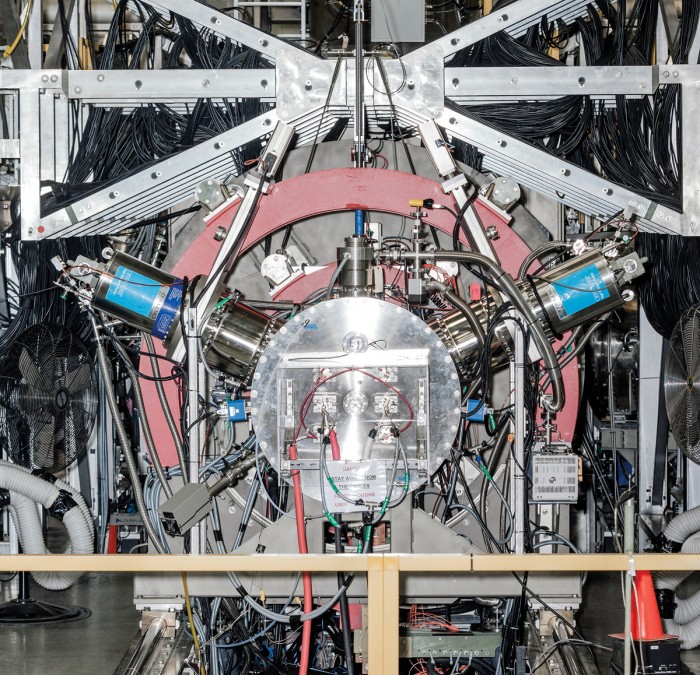

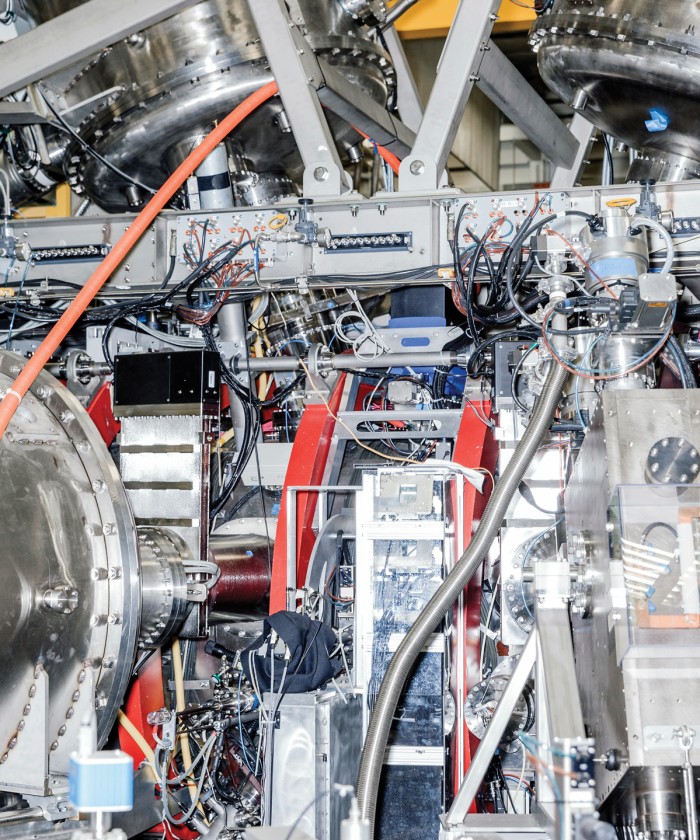

In search of the answers, I visited the headquarters of Tri Alpha Energy in the spring. The coastal fog was lifting from the rolling hills in Foothill Ranch as I stepped inside the building, which houses both Tri Alpha’s offices and its technology lab. A locomotive-sized plasma generator sat surrounded by a dense tangle of scaffolding, sensors, gauges, magnets, instruments, cables, and pipes.

Unlike fission, which splits atoms apart to generate heat in today’s nuclear power plants, fusion smashes atomic nuclei together, releasing huge amounts of energy in the process—the same reaction that occurs in the sun.

For decades, fusion research has involved large, doughnut-shaped machines called tokamaks, which exert powerful magnetic fields to compress the super-hot plasma that contains the atoms to be fused. Those systems have been fiendishly hard to perfect: the director of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor project, which is already years behind schedule, said in April that the fusion reactor would not be switched on until 2025 and would not produce power until at least 2035, requiring overruns of more than $5 billion on top of the $17 billion or so that has already been poured in.

Tri Alpha and a handful of other fusion startups are pursuing different designs that could be simpler and less costly. Tri Alpha’s setup borrows some of the principles of high-energy particle accelerators, such as the Large Hadron Collider, to fire beams of plasma into a central vessel where the fusion reaction takes place. Last August the company said it had succeeded in keeping a high-energy plasma stable in the vessel for five milliseconds—an infinitesimal instant of time, but enough to show that it could be done indefinitely. Since then that time has been upped to 11.5 milliseconds.

The next challenge is to make the plasma hot enough for the fusion reaction to generate more energy than is needed to run it. How hot? Something like 3 billion °C, or 200 times the temperature of the sun’s core. No metal on Earth could withstand such a temperature. But because the roiling ball of gas is confined by a powerful electromagnetic field, it doesn’t touch the interior of the machine.

The photos seen here were taken a few days before Tri Alpha began dismantling the machine to build a much larger and more powerful version that will fully demonstrate the concept. That could lead to a prototype reactor sometime in the 2020s.

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.