Chinese Researchers Experiment with Making HIV-Proof Embryos

Chinese fertility doctors have tried to make HIV-proof human embryos, but the experiments ended in a bust. The new report is the second time researchers in China revealed that they had a go at making genetically modified human embryos.

The controversial experiments are, in effect, feasibility studies of whether it’s possible to make super-people engineered to avoid genetic disorders or resist disease.

“It is foreseeable that a genetically modified human could be generated,” according to Yong Fan, a researcher at Guangzhou Medical University, who published the report.

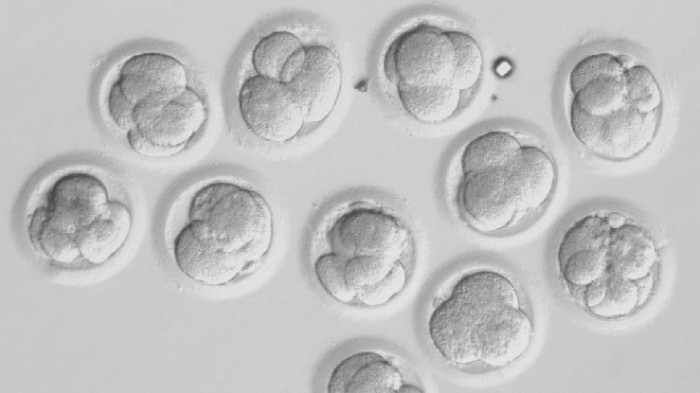

His team collected more than 200 one-cell embryos and attempted to alter their DNA to install a gene that protects against HIV infection. The study, published two days ago in an obscure reproductive journal, was first spotted by reporters at Nature.

The scientists cautioned that they believe making actual genetically modified babies should be “strictly prohibited”—but perhaps only until the technology is perfected. “We believe that is necessary to keep developing and improving the technologies for precise genetic modification in humans,” Fan’s team said, since gene modification could “provide solutions for genetic diseases” and improve human health.

The Chinese scientists tried to make human embryos resistant to HIV by editing a gene called CCR5. It’s known that some people possess versions of this gene which makes them immune to the virus, which causes AIDS. The reason is they no longer make a protein that HIV needs to enter and hijack immune cells.

Doctors in Berlin demonstrated the effect after they gave a man sick from HIV a bone marrow transplant from a person with the protective gene mutation. The man—known since as the “Berlin patient”—was cured of HIV, too.

Using the gene-editing method called CRISPR, Fan and his team tried to change the DNA in the embryos over to the protective version of the CCR5 gene in order to show, in principle, that they could make HIV-proof people.

Almost exactly a year ago, in a world first, a separate group in Guangzhou said that it had altered embryos in an effort to repair the genetic defect that causes a blood disease beta thalassemia.

That set off an ethical debate, and last December the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, along with British and some Chinese scientific leaders, said any attempt to make a gene-edited baby would be “irresponsible,” a message that in many ways seemed directed at IVF doctors in China.

In February, U.S. officials went further, calling gene-editing a “weapon of mass destruction” and making a point of singling out the earlier Chinese research.

One day endowing people with protective genes could become a real possibility. It would be like a vaccine, except one that is installed in a person’s genome from birth. And there’s a long list of genes people might demand for their children in addition to HIV resistance. One DNA change, for instance, seems to completely prevent Alzheimer’s. Another generates people with twice the muscle mass.

But that’s a ways off, and Fan’s team said its experiments essentially flopped. They only managed to successfully edit a handful of embryos, and even these ended up as “mosaics,” or a mix of cells, some of which had the new gene, and some that didn’t.

(Read more: Nature, “Top U.S. Intelligence Official Calls Gene Editing a WMD Threat” “Scientists on Gene-Edited Babies: It’s 'Irresponsible' for Now,” “Chinese Team Reports Gene-Editing Human Embryos”)

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.