How Magic Leap’s Augmented Reality Works

A Florida startup called Magic Leap announced Tuesday that it had received $542 million in funding from major Silicon Valley investors led by Google to develop hardware for a new kind of augmented reality hardware. The secretive startup has yet to publicly describe or demonstrate its technology, and declined an interview request. But patent and trademark filings reveal the kind of technology that Magic Leap plans to use to create what the company’s CEO and founder Rony Abovitz has called “the most natural and human-friendly wearable computing interface in the world.”

The filings describe sophisticated display technology that can trick the human visual system better than existing virtual reality displays (such as the Oculus Rift) into perceiving virtual objects as real. The display technology used in most devices can show only flat, 2-D images. Headsets like the Oculus Rift trick your brain into perceiving depth by showing different images to each eye, but your eyes are always focused on the flat screen right in front of them.

When you look at a real 3-D scene, the depth at which your eyes are focused changes as you look at objects at different distances away. “If we leave out those focus cues we get an experience that’s not quite realistic,” says Gordon Wetzstein, who leads the Computational Imaging Research Group at Stanford University.

Magic Leap’s patents suggest an alternative approach. They describe displays that can create the same kind of 3-D patterns of light rays, known as “light fields,” that our eyes take in from the real objects around us. Wetzstein and other researchers have shown that this allows your eyes to focus on the depths of an artificial 3-D scene just as they would in the real world—providing a far more realistic illusion of virtual objects merged with the real world.

Earlier this year, Wetzstein and colleagues used that technique to create a display that allows text to be read clearly by people not wearing their usual corrective lenses (see “Prototype Display Lets You Say Goodbye to Reading Glasses”). He previously worked on glasses-free 3-D displays based on similar methods. And last year, researchers at chip company Nvidia demonstrated a basic wearable display based on light fields.

A trademark filing from July describes Magic Leap’s technology as “Wearable computer hardware, namely, an optical display system incorporating a dynamic light-field display.”

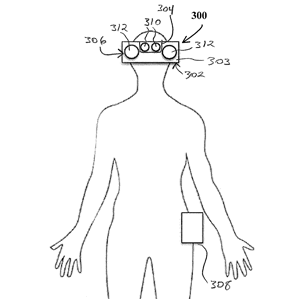

One of Magic Leap’s patents describes how such a device, dubbed a WRAP, for “waveguide reflector array projector,” would operate. The display would be made up of an array of many small curved mirrors; light would be delivered to that array via optical fiber, and each of the tiny elements would reflect some of that light to create the light field for a particular point in 3-D space. The array could be semi-transparent to allow a person to see the real world at the same time.

Multiple layers of such tiny mirrors would allow the display to produce the illusion of virtual objects at different distances. However, Magic Leap’s patent also claims that a single layer of the mirrors would be enough if they were formed from “magnetic liquid.” That would allow the mirrors to be reprogrammed using a magnetic field to rapidly display points at different depths fast enough to fool the eye, like the frames of an animation.

Magic Leap’s greatest challenge may be to find a way to seamlessly integrate virtual 3-D objects created by that display with what a person sees in the real world. Doing so would require the system to sense the world in 3-D and understand exactly what a person is looking at and its exact position, says Wetzstein.

One of Magic Leap’s patents covers the use of motion sensors and eye-tracking cameras on a wearable display to figure out at what depth a person’s eyes are focused. But Wetzstein says he isn’t aware of anyone yet demonstrating a wearable system that can track the distance a person is focusing on.

Another of Magic Leap’s patent filings says that cameras, infrared sensors, and ultrasonic sensors could be used to sense the environment around a person, and to recognize gestures. Depth-sensing cameras are now relatively cheap and compact (see “Intel Says Tablets and Laptops with 3-D Vision Are Coming Soon”). But Wetzstein says Magic Leap will likely need to make major breakthroughs in computer vision software for a wearable device to make sense of the world enough for very rich augmented reality. “They will require very powerful 3-D image recognition, running on your head-mounted display,” he says.

The company is recruiting experts in chip design and fabrication, apparently with a view to creating custom chips to process image data. Dedicated chips could make that work more energy-efficient, something important for a wearable device. Magic Leap already employs Gary Bradski, a pioneer of computer vision research and software, notes Wetzstein. Magic Leap is also trying to recruit people skilled in lasers, mobile and wireless electronics, cameras, manufacturing supply-chain management, 3-D sensing, artificial intelligence, and video game development.

Altogether, many of the underlying techniques Magic Leap needs to realize highly realistic augmented reality have been demonstrated, says Wetzstein. But the company will have to refine and combine them in ways no one has yet managed to do. “I think people are starting to realize this is the future of building consumer devices,” he says. “But it involves big challenges at the intersection of optics, electronics, algorithms, and understanding the human visual system.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.