Google’s Latest Robot Acquisition Is the Smartest Yet

Google’s remarkable push into robotics continued today with the acquisition of Boston Dynamics, a particularly exciting—and potentially important—company.

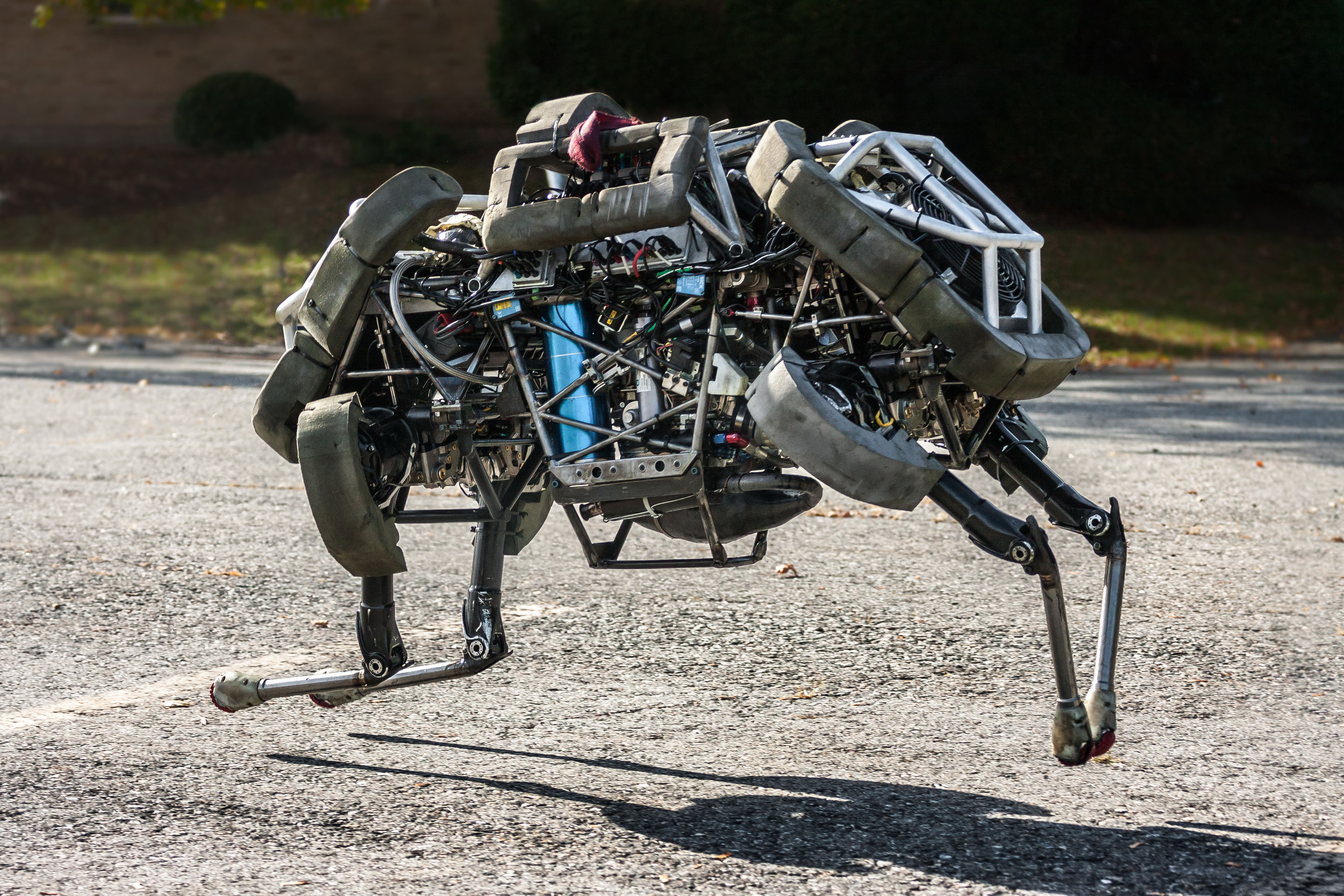

Boston Dynamics creates legged robots with eerily lifelike running and balancing abilities. These machines are more than just spectacular feats of engineering, though; they embody a powerful approach to robot locomotion that might have an big impact on the way future machines move around our world.

Google is making a big drive into robotics. It has acquired seven other other robotics startups in recent months as part of an effort led by Andy Rubin, the man who previously led the development of the Android mobile operating system (see “Why Google Is Buying So Many Robotics Startups”). Google hasn’t yet said what it plans to do with the robotics technologies it has acquired, but they include manipulation, vision, and other areas of innovation that are likely to become increasingly important. Although Boston Dynamics’ machines can bound across wild terrain and run at great speed, the approach the company has pioneered could be useful for more mundane purposes, like climbing a flight of stairs or staying balanced when accidentally shoved.

Boston Dynamics was founded by Marc Raibert, a roboticist who developed a new approach to legged locomotion in the 1980s and led research labs at CMU and MIT dedicated to building walking machines. At a time when most walking robots were rigid and moved slowly, Raibert sought to mimic biology, devising engineering principles that made it possible for machines to remain stable on uneven or treacherous terrain. Like living creatures, Raibert’s robots moved quickly and continually, storing energy in their limbs. His first dynamic robot was a one-legged machine that kept from falling over simply by moving its leg as it bounced around.

Raibert left MIT and founded Boston Dynamics in 1992, initially to develop simulation software. But the company soon began building robots based on his dynamic balancing ideas. Its YouTube videos show the astonishingly lifelike results: a St. Bernard-sized four-legged robot, called BigDog, walking across all sorts of treacherous terrain, and a slightly larger robot, called WildCat, running about the company’s car park at about 30 kilometers per hour. Most recently, Boston Dynamics developed a humanoid robot called Atlas for a DARPA challenge designed to foster the development of robots that can perform rescue missions in environments like Fukushima (see “Meet Atlas, the Robot Designed to Save the Day”). Most of these robots were developed largely with funding from the military.

The technologies developed by Boston Dynamics could be significant because most robots cannot cover uneven terrain. The few mobile robots that exist today, such as the bomb-disposal bots used by the military, tend to travel using wheels or tracks.

In recent weeks I’ve visited Boston Dynamics several times to see Altas, WildCat, and other Boston Dynamics robots in action. Significant challenges remain, including making its hydraulic actuators more efficient and making its robots quieter. But the company is already making impressive strides in these areas.

“It has been a great time at Boston Dynamics, getting the robots this far along,” Raibert told me via e-mail. “Now we are excited to see how far we can take things as part of Google.”

Keep Reading

Most Popular

Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why.

And that's a problem. Figuring it out is one of the biggest scientific puzzles of our time and a crucial step towards controlling more powerful future models.

The problem with plug-in hybrids? Their drivers.

Plug-in hybrids are often sold as a transition to EVs, but new data from Europe shows we’re still underestimating the emissions they produce.

Google DeepMind’s new generative model makes Super Mario–like games from scratch

Genie learns how to control games by watching hours and hours of video. It could help train next-gen robots too.

How scientists traced a mysterious covid case back to six toilets

When wastewater surveillance turns into a hunt for a single infected individual, the ethics get tricky.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.